It has been nearly three weeks since I started with my new employer, Incyte Corporation in Wilmington, Delaware. I am assigned as a clinical statistician focusing on all-phase drug trials in dermatology, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Despite have a name that alludes to a manufacturer of biochemical weapons, Incyte has lived up to its true reputation—a mid-sized pharma company with good benefits and good people. From clinical scientists to chemists to my fellow colleagues in the biostatistics and programming department, everyone has left me with the sense that I can build strong working relationships and do good things, both for the company and its patients.

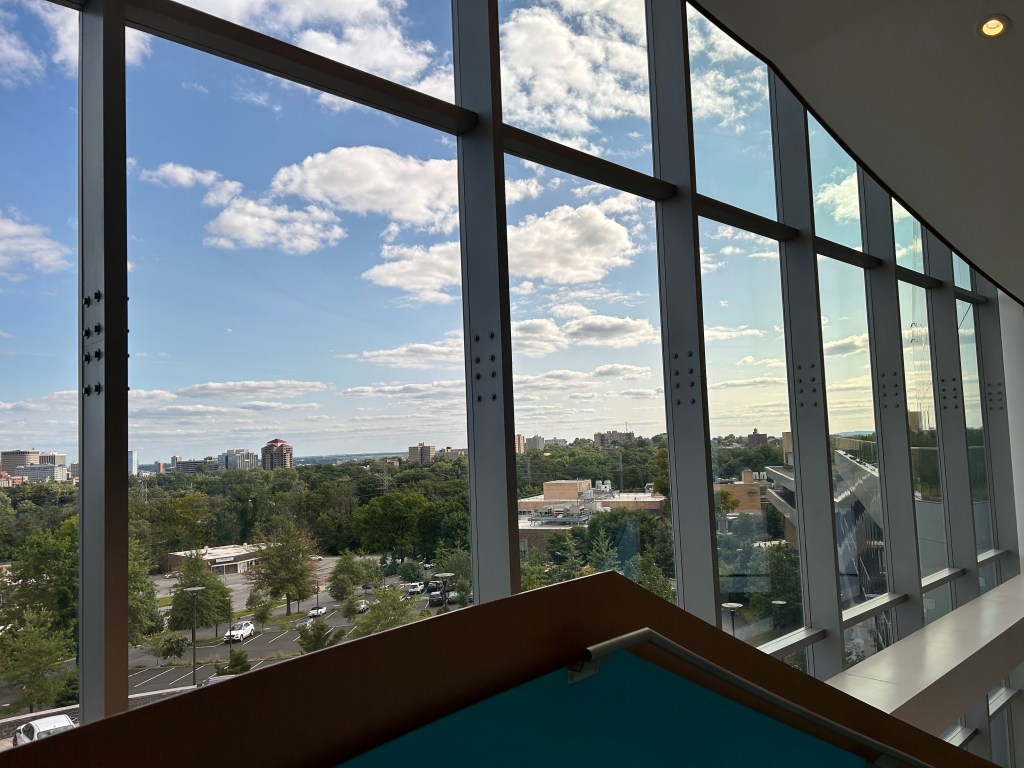

Although Incyte’s firm stance against remote work means that I would come into the office four times a week, I’ve generally enjoyed the in-office days. In particular, I’ve taken advantage of the cafeteria’s discounted food options and seized opportunities to connect with colleagues through casual conversations and events like free ice cream socials.

Reflecting on my first day, it’s clear that life in a corporation is a distant one from that in academia. Intellectually, gone are the cutting-edge research on new statistical methods and the mavericks exploring niche areas. In the world of pharmaceutical clinical development, what has worked before rules supreme, even if it’s something as straightforward as a two-sample proportion test, Pearson’s chi-square test, or ANCOVA. Virtually no one is interested in newly minted but lesser-known methodologies. On the upside, the head-scratching frustrations resulting from tackling difficult math problems, running complex numerical experiments, and diving deep into data solo have also faded. They’ve been replaced by a sense of collegiality. On my first day, our group director made it clear: if something doesn’t seem to work, the best solution is to ask for help rather than trying to figure it out on my own. The key is to get the deliverables ready on time—the practical stuff. Besides, no one wants to delay clinical studies. With dozens of trials at different stages running concurrently, teamwork is essential, involving clinical trial managers, database managers, clinical scientists, medical writers, statistical programmers, and us statisticians. When one person gets stuck, it affects others.

Another lesson I’ve learned is how standardized everything is. There are set procedures for everything—from study design (including the protocol), database transfer, and analysis planning (centered around the famous statistical analysis plan, or SAP), to the actual analysis, reporting, and quality control. Clinical data is collected, stored, transformed, and analyzed according to the omnipresent CDISC (Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium) standard, which requires a deep dive into standard data domains, fields, and terminology. Additionally, most of the programming is done in SAS rather than R. Surprisingly, beyond contributing to protocol design and SAP writing, my main responsibilities as a clinical statistician mainly involve overseeing and quality-controlling various steps in the analysis pipeline and ensuring that everyone grasps the critical concepts and objectives. The bulk of the coding is handled by the statistical programmers based on the SAP specifics. As part of my training, I’ve been put in charge of a phase-2 trial that is about 50% complete, having been worked on by my predecessor, and I’m still learning my role within the ongoing process.

A particularly positive aspect of my experience so far is how supportive everyone on my team has been and the efforts they have taken to make me feel comfortable. From the beginning, my manager and team director clearly communicated their expectations and priorities. The director even told me to be relaxed at work, noting, “If I give you something you can’t complete in time, it’s my failure as a manager.” They’ve also made a point of saying thanks to me whenever possible. During my PhD years, this kind of appreciation was something I seldom experienced from my advisors. At a team lunch yesterday, celebrating the FDA approval of our dermatological cream for treating pediatric atopic dermatitis (eczema)—a project I wasn’t involved in but was still invited to—I had a great time conversing with my manager about our backgrounds and families. Reflecting on my short time here, all these gestures have made me feel incredibly grateful for my co-workers and painted an optimistic picture for my early career.

Leave a reply to A Few Lessons I Learned from My Ph.D. Program – A Statistician's Journey Cancel reply